Table of Contents

Introduction: The Universal Challenge of Pain and the Rise of Specialized Care

Pain is a universal human experience, an intricate alarm system signaling that something is amiss within the body. While often protective, pain can transcend its warning function, becoming a debilitating condition in itself, profoundly impacting physical function, emotional well-being, social interactions, and overall quality of life. Effectively managing pain is not merely a comfort measure; it is a fundamental aspect of compassionate and comprehensive healthcare. Within this critical domain lies the specialized field of pain management nursing, a discipline dedicated to the assessment, treatment, and holistic care of individuals experiencing pain.

The journey of pain management nursing has evolved significantly over the decades. Once considered primarily a symptom to be endured or masked, pain is now recognized as a complex biopsychosocial phenomenon requiring a sophisticated, multidisciplinary approach. Nurses, positioned at the forefront of patient care, play an indispensable role in this process. They are often the first to assess pain, the primary administrators of interventions, the constant monitors of patient response, and the crucial advocates for effective relief.

This guide offers a complete overview of pain management nursing, exploring its core principles, practices, challenges, and the rewarding career path it offers. Understanding the nuances of pain management nursing is essential not only for aspiring specialists but for all healthcare professionals committed to alleviating suffering. The practice of pain management nursing combines scientific knowledge with empathetic care, making it a cornerstone of modern healthcare delivery.

Understanding Pain: The Foundation of Pain Management Nursing

A deep understanding of pain’s multifaceted nature is the bedrock upon which effective pain management nursing is built. Pain is not monolithic; it manifests in various forms, originates from different mechanisms, and is perceived uniquely by each individual.

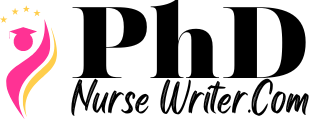

1. Defining Pain:

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) defines pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage.” Key takeaways from this definition relevant to pain management nursing include:

Subjectivity: Pain is always a personal experience influenced by biological, psychological, and social factors. The patient’s self-report is the most reliable indicator of pain.

Sensory and Emotional Components: Pain involves both physical sensation and emotional distress (e.g., fear, anxiety, depression). Effective pain management nursing must address both aspects.

Actual or Potential Damage: Pain can occur even without identifiable tissue damage (e.g., neuropathic pain, fibromyalgia) or can be disproportionate to the degree of injury.

2. Types of Pain:

Understanding the classification of pain guides assessment and treatment strategies in pain management nursing:

- Acute Pain: Typically has a sudden onset, is directly related to tissue injury (e.g., surgery, trauma, burns), serves a protective function, and usually resolves as the underlying cause heals. Effective acute pain management nursing focuses on prompt relief to prevent complications and facilitate recovery.

- Chronic Pain: Pain that persists beyond the expected healing time (often defined as > 3-6 months) or occurs in association with a chronic condition (e.g., arthritis, neuropathy, cancer). It often loses its protective function and becomes a disease state in itself. Chronic pain management nursing requires long-term strategies, focusing on functionality, coping mechanisms, and quality of life.

- Nociceptive Pain: Arises from the stimulation of nociceptors (pain receptors) by actual or potential tissue damage.

- Somatic Pain: Originates from skin, muscles, bones, joints (e.g., incision pain, bone fractures). Often described as sharp, aching, or throbbing.

- Visceral Pain: Originates from internal organs (e.g., pancreatitis, appendicitis). Often described as deep, cramping, squeezing, or pressure-like, and may be poorly localized or referred to other areas.

- Neuropathic Pain: Caused by damage or dysfunction of the peripheral or central nervous system. Often described as burning, shooting, stabbing, tingling, numbness, or electrical sensations (e.g., diabetic neuropathy, post-herpetic neuralgia, phantom limb pain). It frequently responds poorly to traditional analgesics, requiring specific approaches within pain management nursing.

- Cancer Pain: Can be acute or chronic, nociceptive or neuropathic, or a combination. Often related to the tumor itself, cancer treatments (surgery, radiation, chemotherapy), or co-existing conditions. Specialized pain management nursing is crucial in oncology.

3. The Pain Pathway:

Understanding the basic physiology helps pain management nursing professionals target interventions:

Transduction: Noxious stimuli (mechanical, thermal, chemical) are converted into electrical signals by nociceptors.

Transmission: Pain signals travel along nerve fibers (A-delta and C fibers) to the spinal cord and then ascend to the brain.

Perception: The brain interprets the signals as pain. This is a complex process influenced by attention, emotion, memory, and cultural factors.

Modulation: The nervous system can inhibit or amplify pain signals at various points along the pathway (e.g., through descending inhibitory pathways involving endorphins).

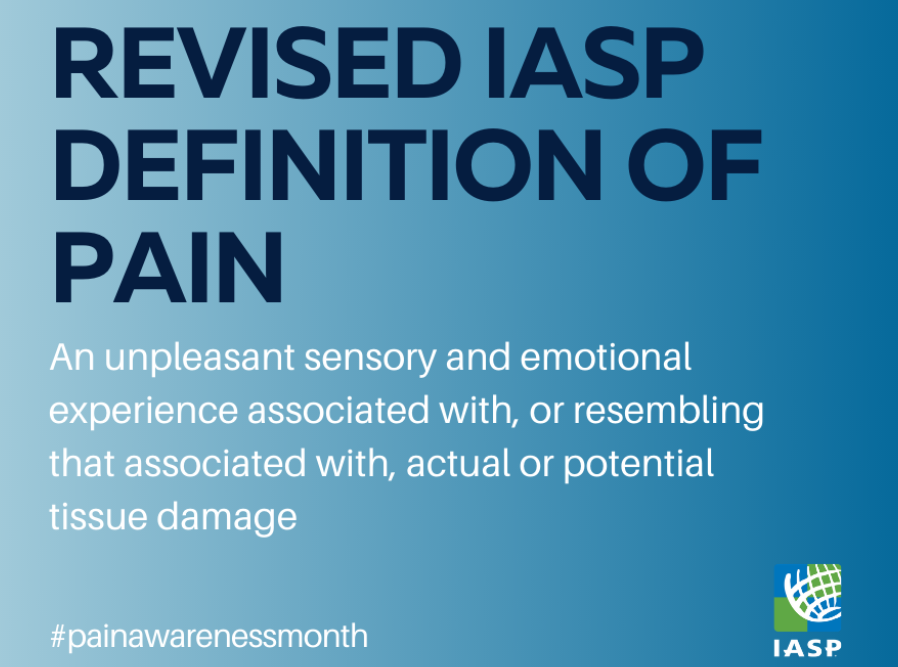

The Indispensable Role of the Pain Management Nurse

The pain management nurse is a highly skilled registered nurse (RN) who specializes in the care of patients experiencing pain. Their role extends far beyond medication administration, encompassing a broad spectrum of responsibilities critical to achieving optimal patient outcomes. Effective nursing pain management requires a unique blend of clinical expertise, communication skills, critical thinking, and compassion.

Core Responsibilities and Skills:

- Comprehensive Pain Assessment: Performing thorough, ongoing assessments of pain intensity, location, quality, characteristics, and its impact on function and mood. This is the cornerstone of pain management nursing.

- Developing Individualized Care Plans: Collaborating with the patient, family, and interdisciplinary team (physicians, pharmacists, physical therapists, psychologists) to create tailored pain management plans.

- Implementing Pain Interventions: Administering pharmacological agents (opioids, non-opioids, adjuvants) via various routes, monitoring for efficacy and side effects, and skillfully implementing non-pharmacological strategies. Competent pain management nursing integrates multiple modalities.

- Evaluating Treatment Effectiveness: Continuously monitoring patient responses to interventions, adjusting the care plan as needed based on reassessments. This iterative process defines dynamic pain management nursing.

- Patient and Family Education: Teaching patients and their families about the nature of their pain, the treatment plan, medication use (including safe storage and disposal), potential side effects, self-management techniques, and realistic expectations. Education is a vital component of pain management nursing.

- Patient Advocacy: Championing the patient’s right to adequate pain relief, communicating concerns to the healthcare team, and challenging biases or misconceptions about pain. Advocacy is central to the ethos of pain management nursing.

- Coordination of Care: Facilitating communication and collaboration among all members of the healthcare team involved in the patient’s pain management.

- Documentation: Maintaining accurate and detailed records of assessments, interventions, patient responses, and communication, which is crucial for continuity of care and legal protection in pain management nursing.

- Utilizing Technology: Employing tools like Patient-Controlled Analgesia (PCA) pumps, epidural catheters, intrathecal pumps, and neuromodulation devices, requiring specific technical skills within pain management nursing.

- Staying Current: Keeping abreast of the latest evidence-based pain management practices, guidelines, medications, and technologies through continuing education.

The scope of pain management nursing can range from bedside care in hospitals and hospices to specialized roles in outpatient pain clinics, rehabilitation centers, and primary care settings.

Comprehensive Pain Assessment: The Starting Point

Accurate and thorough assessment is paramount in pain management nursing. It guides diagnosis, treatment selection, and evaluation of effectiveness. The adage “pain is what the patient says it is” underscores the importance of believing the patient’s report.

Key Components of Pain Assessment:

- Self-Report: The gold standard whenever possible. Use appropriate pain intensity scales:

- Numeric Rating Scale (NRS): 0-10 scale (0 = no pain, 10 = worst possible pain).

- Verbal Descriptor Scale (VDS): Uses words like “no pain,” “mild,” “moderate,” “severe.”

- Faces Pain Scale-Revised (FPS-R): Uses validated facial expressions, suitable for children and some adults with communication difficulties.

- Visual Analog Scale (VAS): A 10cm line where the patient marks their pain level.

- PQRSTU Mnemonic (or similar framework):

- Provoking/Palliating factors: What makes it better or worse?

- Quality: Describe the pain (e.g., sharp, dull, burning, aching).

- Radiation/Region: Where is the pain? Does it spread?

- Severity/Intensity: Use a validated scale.

- Timing/Treatment: When did it start? Is it constant or intermittent? What have you tried?

- U: How does it affect U? (Impact on function, sleep, mood, activities).

- Assessment in Non-Verbal Patients: This is a significant challenge in pain management nursing. Requires careful observation of behavioral cues:

- Facial expressions (grimacing, frowning).

- Vocalizations (moaning, crying, groaning).

- Body movements (restlessness, guarding, rigidity).

- Changes in interaction patterns (withdrawal, combativeness).

- Changes in vital signs (though less reliable, can be supplementary).

- Use validated behavioral pain scales (e.g., CPOT for critical care, PAINAD for advanced dementia).

- Functional Assessment: How does pain interfere with daily activities, work, sleep, appetite, and social interactions? Assessing function provides objective markers of pain impact and treatment success.

- Psychosocial Assessment: Explore the emotional impact of pain (anxiety, depression, fear, anger) and social factors (support systems, cultural beliefs about pain). Holistic pain management nursing considers these factors.

- Reassessment: Pain is dynamic. Regular reassessment after interventions (e.g., 30-60 minutes post-medication) is crucial to evaluate effectiveness and adjust the plan. This is a non-negotiable aspect of safe pain management nursing.

Pain Management Strategies: The Nurse’s Toolkit

Effective pain management nursing utilizes a multimodal approach, combining pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions tailored to the individual patient’s needs, type of pain, and clinical context. The following are the main pain management strategies.

1. Pharmacological Interventions:

Nurses play a key role in administering medications, monitoring effects, managing side effects, and educating patients.

- Non-Opioid Analgesics:

- Acetaminophen (Paracetamol): Effective for mild-to-moderate pain, antipyretic. Generally well-tolerated but carries risk of hepatotoxicity with overdose. Pain management nursing includes educating patients about maximum daily doses and hidden sources in combination products.

- Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): (e.g., ibuprofen, naproxen, ketorolac, celecoxib). Effective for mild-to-moderate pain, particularly inflammatory pain. Potential side effects include GI bleeding, renal impairment, and cardiovascular risks. Careful assessment of contraindications is essential in pain management nursing.

- Opioid Analgesics:

- Mechanism: Bind to opioid receptors in the CNS and periphery to block pain signals. Effective for moderate-to-severe pain, particularly acute and cancer pain.

- Classification: Weak (e.g., codeine, tramadol) and Strong (e.g., morphine, hydromorphone, fentanyl, oxycodone).

- Routes: Oral, IV, IM, SC, transdermal, rectal, epidural, intrathecal.

- Key Nursing Considerations: High potential for side effects (respiratory depression, sedation, constipation, nausea/vomiting, pruritus, urinary retention). Pain management nursing requires vigilant monitoring, proactive management of side effects (especially constipation), and understanding of tolerance, physical dependence, and addiction risk. The opioid crisis necessitates judicious prescribing, patient education on risks, safe storage/disposal, and consideration of non-opioid alternatives. Equianalgesic dosing is important when switching opioids or routes.

- Adjuvant Analgesics:

- Medications with primary indications other than pain but found effective for certain pain types, especially neuropathic and chronic pain.

- Antidepressants: (e.g., TCAs like amitriptyline, SNRIs like duloxetine, venlafaxine). Useful for neuropathic pain, fibromyalgia.

- Anticonvulsants: (e.g., gabapentin, pregabalin). First-line for many neuropathic pain conditions.

- Corticosteroids: Reduce inflammation and edema (e.g., dexamethasone for cancer pain related to nerve compression).

- Muscle Relaxants: For pain associated with muscle spasm.

- Topical Agents: (e.g., lidocaine patches, capsaicin cream). Localized relief with minimal systemic absorption.

- Pain management nursing involves understanding the rationale, dosing, and side effects of these diverse agents.

2. Non-Pharmacological Interventions:

These strategies are essential components of integrated pain management practices and can reduce reliance on medication, improve coping, and enhance overall well-being. Pain management nursing professionals should be knowledgeable and skilled in implementing or facilitating these therapies:

- Physical Modalities:

- Heat/Cold Therapy: Superficial heat can relax muscles; cold can reduce inflammation and numb the area. Requires careful application to prevent tissue damage.

- Massage: Can reduce muscle tension, improve circulation, and promote relaxation.

- Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS): Delivers low-voltage electrical currents through skin electrodes to modulate pain signals.

- Positioning/Movement: Proper body alignment, assistive devices, gentle exercise, physical therapy can alleviate pain and improve function.

- Cognitive-Behavioral Strategies:

- Distraction: Focusing attention away from pain (e.g., music, conversation, games, guided imagery).

- Relaxation Techniques: Deep breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, meditation, mindfulness.

- Guided Imagery: Creating calming mental images.

- Biofeedback: Learning to control physiological responses (e.g., muscle tension, heart rate).

- Cognitive Restructuring/CBT: Identifying and changing negative thought patterns related to pain.

- Psychological/Spiritual Support:

- Addressing anxiety, depression, fear associated with pain.

- Providing emotional support, validating the patient’s experience.

- Facilitating access to counseling, support groups, or spiritual care.

- Integrative Therapies:

- Acupuncture/Acupressure: Stimulation of specific points on the body.

- Yoga/Tai Chi: Mind-body practices involving movement, breathing, and meditation.

- Aromatherapy: Use of essential oils for relaxation or symptom relief.

A cornerstone of skilled pain management nursing is the ability to integrate these varied approaches into a cohesive, patient-centered plan.

Education and Advocacy: Empowering Patients and Colleagues

Education and advocacy are integral functions of pain management nursing:

- Patient/Family Education: Empowering patients with knowledge about their pain condition, treatment options (pharmacological and non-pharmacological), how to use medications safely, potential side effects, self-management strategies, and realistic goals is critical for adherence and successful outcomes. Skilled pain management nursing involves tailoring education to individual learning needs.

- Interprofessional Education: Educating other nurses, physicians, and healthcare professionals about best pain management practices, assessment tools, overcoming barriers to effective pain relief, and challenging myths or biases.

- System-Level Advocacy: Pain management nurses can contribute to developing institutional policies, protocols, and quality improvement initiatives related to pain management. They can advocate for resources and support for comprehensive pain care.

Challenges and Future Directions in Pain Management Nursing

Despite advancements, significant challenges remain in the field:

- The Opioid Crisis: Continues to influence prescribing practices, sometimes leading to “opiophobia” and undertreatment of legitimate pain. Finding the right balance remains a major hurdle for pain management nursing.

- Undertreatment of Pain: Persists due to various factors including inadequate assessment, lack of knowledge, biases, systemic barriers, and patient reluctance to report pain or take medication.

- Lack of Access: Disparities exist in access to specialized pain care, particularly for rural populations and underserved communities.

- Chronic Pain Epidemic: The growing prevalence of chronic pain necessitates more effective, sustainable, and holistic management strategies beyond just medication.

- Research Gaps: More research is needed, particularly on chronic pain mechanisms, non-pharmacological interventions, and long-term outcomes.

Becoming a Pain Management Nurse: Pathway to Specialization

Pursuing a career in pain management nursing typically involves several steps:

- Become a Registered Nurse (RN): Earn an Associate Degree in Nursing (ADN) or a Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) and pass the NCLEX-RN exam. A BSN is often preferred or required for certification and advanced roles.

- Gain Clinical Experience: Obtain experience in areas like medical-surgical nursing, critical care, oncology, orthopedics, or palliative care, developing foundational assessment and clinical skills.

- Seek Specialization:

- Certification: Obtain specialty certification, such as the Pain Management Nursing Certification (PMGT-BC™) offered by the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC) or credentials through the American Society for Pain Management Nursing (ASPMN). This typically requires specific practice hours in pain management and passing a rigorous exam, demonstrating expertise in pain management nursing.

- Continuing Education: Engage in ongoing education specific to pain assessment, pharmacology, non-pharmacological methods, and emerging trends. Attending conferences and workshops related to pain management nursing is beneficial.

- Advanced Education (Optional but Recommended for Leadership/Advanced Practice):

- Pursue a Master of Science in Nursing (MSN) or Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) with a specialization or focus relevant to pain management (e.g., Adult-Gerontology Nurse Practitioner, Clinical Nurse Specialist).

- Advanced academic work may culminate in significant research contributions. Completing a dissertation about pain management nursing for a PhD or a pain management nursing thesis for a Master’s degree adds valuable knowledge to the field, often exploring specific pain management practices or patient outcomes. At PhD Nurse Writer, we can deliver an authentic and impactful nursing dissertation for academic and professional excellence. Besides dissertations, we also assist students with assignments, term papers, ATI-TEAS tests, research papers, thesis and case studies.

Conclusion: The Art and Science of Alleviating Suffering

Pain management nursing is a dynamic, challenging, and profoundly rewarding specialty. It stands at the intersection of science, requiring deep knowledge of physiology, pharmacology, and assessment techniques, and art, demanding empathy, communication, advocacy, and the ability to build trusting relationships with patients often at their most vulnerable. The role of the pain management nurse is critical in alleviating suffering, improving function, enhancing quality of life, and ensuring that pain is treated with the seriousness and compassion it deserves.

From the bedside in acute care to specialized clinics managing chronic conditions, pain management nursing professionals make a tangible difference every day. As our understanding of pain continues to evolve, the expertise and dedication of those practicing pain management nursing will become even more vital in meeting one of healthcare’s most fundamental challenges. The commitment to continuous learning, evidence-based practice, and patient-centered care defines the excellence inherent in the field of pain management nursing. It is a specialty that truly embodies the core values of nursing: care, compassion, and competence in the face of human suffering. Effective pain management nursing transforms patient experiences and outcomes.